Civil War Meets Mid-Century Modern

By Kendall Curlee

National Park Service

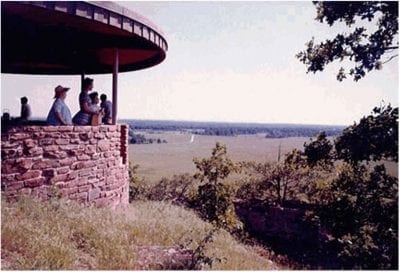

With its sleek, Jetson-esque curves, the overlook at Pea Ridge Military Park looks like it could have beamed down from Saturn. Built in 1956 as part of the “Mission 66” federal initiative to modernize national parks, it affords stunning views of a battlefield where the Union army won a decisive victory over Confederate forces.

But the mid-century modern structure, still pleasing to 21st-century tastes, landed on a historically sensitive site.

“The overlook was built right on top of the bluffs where Confederate soldiers tried to take shelter during the barrage,” said Addison Warren, an honors landscape architecture student. “They ended up being massacred because of ordinance bouncing off the rocks.” The overlook’s tone-deaf siting was characteristic of Mission 66 design, which emphasized natural resources at the expense of cultural and historical artifacts. At Pea Ridge and elsewhere, architects tore down old homesteads, eradicated farms, and rerouted traffic circulation to create serpentine parkways punctuated by scenic overlooks.

“Mission 66 coincided with the auto boom, and the car became the primary ‘driver’ of the landscape design,” Warren said with a grin. “At Pea Ridge, you don’t even have to get out of your car.”

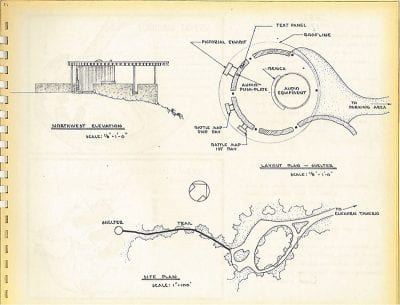

National Park Service Plan, ca. 1964, for the East Overlook

at Pea Ridge National Park; Mission 66-era photos of the park.

Warren’s connection with Pea Ridge goes way back. His forebears fought on both sides of the Civil War and a visit to the park at age 10 made a strong impression. “In 8th grade I made a diorama of Pea Ridge and I have loved the site since – I’ve always wanted to do something with it,” he said. When he came to the University of Arkansas to study landscape architecture, he hoped to link his love for history and the outdoors.

That connection happened early in his second year, when he took the first of a series of courses with Kimball Erdman, an associate professor of landscape architecture who focuses on the preservation of endangered cultural landscapes. That first class focused on a homestead, hotel and store in Rush, Arkansas, located in the heart of the Buffalo National River area. A stone wall and steps are among the scant remains, but Erdman and his students mined historic records, newspaper clippings and aerial photos to document and digitally recreate the site.

“That’s where I really fell in love with landscape preservation and decided, ‘yes, this is what I want to do,’” Warren said. Erdman subsequently hired him and one other student to document the site in Rush. Their efforts won an honor award from the Arkansas chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects and an honorable mention from Preserve Arkansas. That project also gave Warren the expertise needed to tackle honors thesis work on Pea Ridge.

He began his research by compiling a database of documents, articles and photos that would be a springboard to the next phase, a design project undertaken with fellow student Alexander Holyfield.

“I asked them to explore two very different approaches,” Erdman said. In the first, they were asked to rehabilitate Pea Ridge’s Mission 66 design, retaining the loop road but changing it to be more sensitive to the 19th-century cultural landscape. In the second, they would redesign the park as a pedestrian experience. “What if Alex and Addison had been able to design the park in the 50s? In other words, throw out Mission 66 and do it right.”

National Park Service

The adaptive reuse of Mission 66 is very likely the way forward for Pea Ridge, as it retains the many layers of culture embedded in the site, including the car-centric ’50s when the park was built. But the second option sparked some of the most original design thinking. For example, the students proposed a visitor center where a long glass wall would present digital recreations of battles and stagecoaches passing by on Telegraph Road (which forms part of the Butterfield Overland Mail route).

“With augmented reality, we can make the past come alive, and that’s something I’d like to explore if I go into the National Park Service,” Warren said.

For his honors thesis, Warren completed a Historic American Landscape Survey (HALS) on Pea Ridge. The HALS is a comprehensive tool to document historic landscapes that includes a broad overview of the historic context, a detailed description of the existing condition of the site, and supporting photos and drawings. Over three semesters of independent study with Erdman, Warren compiled an 85-page, single-spaced report on Pea Ridge, still peppered with red ink corrections when we sat down to visit.

“This is a professional report,” Erdman said. “It will go to the client, and it will also be submitted to the National Park Service in Washington, D.C. They will review it, then put it in the Library of Congress, where it will be available to everyone, forever.”

Warren has presented his work with Erdman and other students at four conferences, most recently presenting his thesis research at the 2018 Arkansas College Art History Symposium in Fayetteville. Following graduation in May, he began an internship at Guadalupe Mountains National Park in west Texas. He also will work with Erdman to complete a Cultural Landscape Inventory for Carlsbad Caverns National Park in southern New Mexico before pursuing graduate studies in historic preservation.

More Field Notes Stories

Reading Renaissance Portraits

Clio Rom links Petrarch’s poetry with static, idealized profile portraits. Neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino, who believed that looking into a woman’s eyes could inspire a divine frenzy, may have prompted the shift to three-quarter views. Here, Rom walks us through three portraits that signify a sea change in Renaissance art, literature and philosophy.

Hydroponic Profits

Honors students Sarah Gould and Laura Gray stand between two wooden stakes embedded in the ground at local community garden Tri Cycle Farms. Today the empty space holds a vision: a greenhouse for hydroponically grown vegetables that will generate profits, and a sustainable future, for the farm. Gould and Gray’s honors theses in biological engineering will help transform this vision into reality.

A Champion for Cultural Competency

Marshall Islanders have moved from a culture where the sick consult healers and pastors into health care marked by waiting rooms, co-pays, and often complicated jargon. Many people in Northwest Arkansas pass them in the grocery store, at a bus stop, or in a doctor’s office, but never truly understand who they are and where they have come from.

Market Entry Masala

Nine cities. 14 days. 23 meetings. It’s an eye-popping schedule, but for accounting and finance major Grayson Greer, it was a bold way to jump-start research on his honors thesis. He designed the two-week trip to India himself, intent on identifying a unified strategy for entering the Indian food and beverage market.

Queens of the Jungle

Senior honors students Kelsey Johnson and Mersady Redding were traipsing through the Belizean jungle one day when they heard low grunts nearby. Stooping down, hoping for a sighting of wild pigs, the two women and their three guides suddenly fell victim to an onslaught of sticks hurled at them from above.