The path over the Pyrenees is lined with wild garlic, the air pungent with the smell. The trail winds upward through a rich forest of fir and birch, over muddy banks and swift-flowing streams. Feet stamp out a steady rhythm as students chat about subjects ranging from Star Wars to the reintroduction of Slovenian black bears to this region of France.

The path over the Pyrenees is lined with wild garlic, the air pungent with the smell. The trail winds upward through a rich forest of fir and birch, over muddy banks and swift-flowing streams. Feet stamp out a steady rhythm as students chat about subjects ranging from Star Wars to the reintroduction of Slovenian black bears to this region of France.

After a few kilometers of gentle climbing, we stop before the ruined 12th century foundation of an ancient “hospital,” a place of rest and recovery for medieval pilgrims. To the west, we notice the weather turning: the snow-capped mountains, glowing with a matte brilliance just minutes before, are enshrouded by gray, misty clouds. A few moments later thunder rumbles in the distance. The temperature drops and the day grows dark; soon, the rain begins. Before we know it we’re soaked, hiking through now-swampy grasslands and slipping over streams already swollen with late snowmelt. Despite the circumstances, the students are all in high spirits, laughing and grinning through sheets of rain. Curtis Worley channels the Count of Toulouse, ostensible heretic, waving the flag of the Languedoc region of France and leading the charge through the trees. Dani Carson and Jack Williams break into a run as the final climb over the pass comes into view.

After a few kilometers of gentle climbing, we stop before the ruined 12th century foundation of an ancient “hospital,” a place of rest and recovery for medieval pilgrims. To the west, we notice the weather turning: the snow-capped mountains, glowing with a matte brilliance just minutes before, are enshrouded by gray, misty clouds. A few moments later thunder rumbles in the distance. The temperature drops and the day grows dark; soon, the rain begins. Before we know it we’re soaked, hiking through now-swampy grasslands and slipping over streams already swollen with late snowmelt. Despite the circumstances, the students are all in high spirits, laughing and grinning through sheets of rain. Curtis Worley channels the Count of Toulouse, ostensible heretic, waving the flag of the Languedoc region of France and leading the charge through the trees. Dani Carson and Jack Williams break into a run as the final climb over the pass comes into view.

Amelia Holcomb, a freshman journalism and political science major, is grateful for the hike, and the weather. “To experience the physical aspects of the Camino for a little bit, especially with the rain, I think it gave us an appreciation for what the pilgrims would have gone through.”

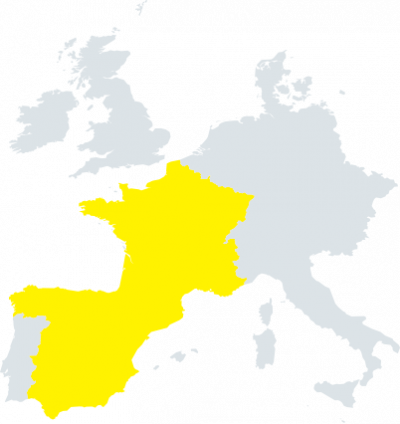

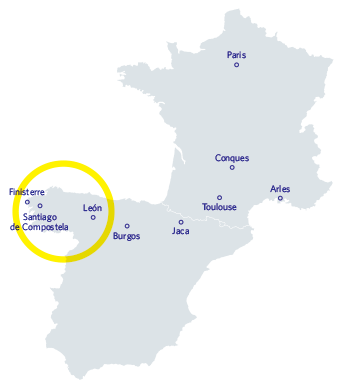

This is the Camino de Santiago. Not the spiritual hotspots or religious reliquaries that pepper the trail, but the physical, experiential filament that connects them all: the 18-inch-wide strip of earth that for centuries has guided both religious and secular pilgrims through France to Spain, each step carrying them that much closer to Santiago de Compostela, the city of Saint James.

Santiago is our ultimate destination, as we follow in the footsteps of those pilgrims who came before and walk beside modern-day pilgrims as they make their way along the medieval path. The 18 honors students participating in Honors Passport: Pilgrimage, a two-week intensive intersession study abroad program, are no strangers to this part of the world. For many of them this trip marks their first experience abroad, their first plane ride, their first contact with non-Anglophone cultures, yet they are already familiar with the places they visit. Each of them spent the weeks prior to the pilgrimage researching various sites and people of the trail as well as the mythologies that grew up around them along the Camino. They became experts in backstories, architectural features, religious intrigue and political exigence. During this trip, they will be presenting their research on-site while they experience the Camino both as scholars and as pilgrims themselves.

The Head and the Heart

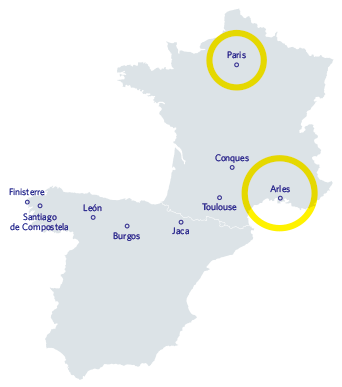

Their journey begins in Paris, where no amount of jetlag could overshadow the wonder of the city streets: the people, the noise, the shopping, the dining – and the incongruity. Students marvel at the architectural extremism of the city, the juxtaposition of the stark, utilitarian beige-gray concrete and the ornate, the Gothic, the ostentatious, all coalescing into the utter uniqueness of the Parisian skyline. Here, the past is present in a way not seen at home, deep-cut tradition melding effortlessly into modern ritual.

Their journey begins in Paris, where no amount of jetlag could overshadow the wonder of the city streets: the people, the noise, the shopping, the dining – and the incongruity. Students marvel at the architectural extremism of the city, the juxtaposition of the stark, utilitarian beige-gray concrete and the ornate, the Gothic, the ostentatious, all coalescing into the utter uniqueness of the Parisian skyline. Here, the past is present in a way not seen at home, deep-cut tradition melding effortlessly into modern ritual.

Jackson Williams, a sophomore art history and international studies major, quickly picks up on this almost mystical dynamism. “Whether you’re super spiritual or not, there’s this feeling of historical precedence everywhere you go along the Camino,” he reflects. “You can just feel the energy of a thousand years of people walking and experiencing the same thing.”

Lynda Coon, a medieval historian and dean of the Honors College, and Kim Sexton, a professor of architectural history, drive home this continuity, ensuring that the students are aware that by participating in this course, they are becoming themselves a part of this history. “You’re sitting right where the medieval pilgrims probably sat,” Dean Coon says during an impromptu lecture at the Roman cemetery of Alyscamps in Arles, where the students perch on a low wall surrounded by 1,000-year-old tombs. Thanks to several local saints, Arles was an important starting point along the Camino.

“This is an experience of what real medieval cities were like,” Sexton says, referencing the hodge-podge of architectural styles in the cemetery. “We’ve seen three of the most important Gothic structures in Paris, so now we can see how Alyscamps differs. Your eyes are getting developed.”

“Dr. Sexton has taught us well about how architecture speaks,” Jacob Huneycutt says. And these students have learned its language well; they explore Alyscamps and its church like full-fledged scholars, marveling at its mélange of styles: pointed Gothic archways juxtaposed with rounded Romanesque ones; tiny Romanesque windows beside hideous Gothic gargoyles; the odd construction of a vaulted half-rose window. They converse about the carvings on the tombs – what they symbolize, and probable dates for the inscriptions. They’ve been reading history for months on the page; now they relish reading it live.

But then something unexpected happens: echoes of song emanate from a small side chapel, as music professor Nikola Radan leads the pilgrimage band in an a cappella rendition of several Cantigas de Santa Maria, canticles attributed to 13th-century Castilian King Alfonso X. These songs of praise were sung along the Camino, and here in Alyscamps time stops as our own pilgrims bring them to life.

The students are drawn to Susan Tucker’s soaring voice. The intangibility of spiritual pilgrimage takes over, silencing, at least for now, all analytical processing. As the trip continues, this phenomenon becomes familiar: historical analysis is tempered by an admixture of awe and emotion, reminding the students that this is not only an academic journey, but also a spiritual one.

“Knowing that I was singing medieval worship songs in a place where they would have actually been performed changed the whole experience. … It may have been an empty stone room, but it seemed to come alive again. It was chilling to hear the music the way it was meant to be performed,” Tucker says.

Medieval Marketing and Tourism Today

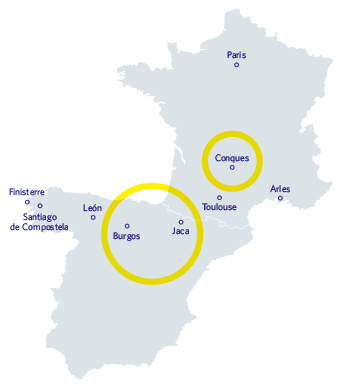

Nowhere is the effect of the cantigas more palpable than in Conques, a small town nestled in the sleepy hills of southern France. Home to only 90 residents, it attracts more than 1 million visitors a year, thanks in large part to the grandeur of the Romanesque Abbey Church of St. Foy. The pilgrimage band was granted the opportunity to perform within this cavernous structure, and afterward, recounts Tucker, “The priest actually asked us to come back and sing later for some real pilgrims, and that was really special because we were able to share something with them. It would have been a lot like that in the Middle Ages.”

“My French horn was a lot to lug around Europe,” Jacob Purifoy laughs, “but when we did get to play, I think we did a lot for the crowds that gathered around us. … They were really drawn to hear that message of pilgrimage, and I think that was cool, that we could provide that both for them, and for our own group.”

“You are not tourists,” Brother Pierre Adrien gushes to the students after their late-night performance. This is a compliment, but in truth tourism is and was one of the principle perks for towns along the pilgrimage path. During the advent of the Way of Saint James, every small town advertised their local martyrs, cathedrals and cemeteries to attract pilgrims and benefit from the economy of the weary traveler, who was usually more than happy to pay at the very least for a hot meal and a warm bed.

Medieval pilgrims were especially attracted to those who sacrificed their lives for their faith, as Dean Coon explains in Alyscamps: “Martyrs would be an axis mundi, a pillar connecting this site to the heavens. They existed in both realms, so to be near the martyrs is to have a glimpse into paradise.”

For this reason, the head reliquary of 12-year-old martyr St. Foy is a huge draw for those visiting Conques.

“Head reliquaries are unique because they provide a connection between the people looking at the reliquary and the reliquary looking back, in addition to serving as intermediary between the believer and God,” says Tenley Getschman, a sophomore economics and international studies major who presented on the saint. “She’s such a dynamic figure, I can understand how pilgrims would come and be so enamored by her.”

St. Foy was known for performing miracles – giving sight to the blind, raising animals from the dead – and for punishing sinners, most famously with paralysis. “You see all these people being tortured,” Elizabeth Cooper, a sophomore history and anthropology major, points out during her presentation on the tympanum of the church, with its vivid depictions of sinners being roasted alive, strung up by their necks and suffering even more gruesome punishments. “But the figures are blank. Amid the powerlessness to control their bodies, they transfer their pain and suffering to the soul.”

Medieval pilgrims would have been drawn to these architectural figures and the stories they told, warnings against sin and reinforcements of the pilgrims’ will to continue their weary journey to Santiago. Today, Conques continues to welcome and refresh travelers by offering daily concerts and blessings for the pilgrims, like the one at which our band performed.

Ladies, Not Gentlemen

On the opposite side of the Pyrenees we discover a very modern narrative, and an unlikely one to encounter in medieval history: women in power. In what is now the province of Castile and León in northern Spain, queens and abbesses ruled with authority; when challenged, they fought back. These figures have crafted a legacy that has inspired women through the centuries, including many of our own students.

The Abbey of Santa María la Real de las Huelgas in Burgos, Spain, was the seat of much of this inspirational activity. “I can feel the girl power here,” someone says as we file into the courtyard.

Darci Walton, a sophomore history and Spanish major, overhears. “Men did not exist in this place!” she exclaims with pride. Walton is presenting on Las Huelgas and has been studying the convent for three months prior to the pilgrimage trip. “I’ve been obsessed,” she says.

This abbey was established in the 12th century by Alfonso VIII of Castile at the behest of his wife, Eleanor Plantagenet, daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and was run by royal abbesses for hundreds of years. The structure became known for sheltering pilgrims in its famous hospital, and later became known as the “Mother” of all Cistercian houses of women in Castile and León.

Women in the north of Spain enjoyed an unprecedented amount of power in the Middle Ages. Case in point: the royal abbesses at Santa Maria de las Huelgas controlled local tax and legal systems, educated the royal family and governed 14 major cities and 15 towns. “This was monumental at the time, especially for women,” Walton emphasizes. “You answered to the nuns. They only used the men for signatures.”

We see similar displays of power in León, where Dani Carson, a junior biology major, presents on the Basilica of San Isidoro, which Queen Urraca of Zamora embellished to propagandize for the royal family. “Now we get into some juiciness,” Carson begins, “because there was some drama in this family; some murderous drama.” Legend has it that Urraca arranged for the murder of her own half-brother Sancho, the illegitimate son of a Moorish mother, to prevent the usurpation of her power. She later immortalized her family’s power dynamics by selecting an unusual scene for the portal of San Isidoro: the Sacrifice of Isaac. Scholars suggest that Sancho is represented in the portal by Ishmael, Abraham’s son by his second wife. Isaac, Abraham’s “legitimate” first son, likely represented Alfonso VI, Urraca’s brother and co-conspirator, and heir to their father’s kingdom.

“You can’t make this stuff up,” Dean Coon comments.

Just as the French kings used their cathedrals and programs of stained glass to underscore their power and equate the crown with the church, Urraca embedded herself symbolically into the murals and carvings of the basilica itself, as a testament to her own authority. She even had her own name engraved into the purported Holy Grail, an artifact that was already 1,000 years old when it came into her hands. “She was a little power-hungry,” Carson laughs, “but she was amazing.”

At the End of the Earth

Finally, after two long weeks of early mornings, late nights, hikes and bus rides, the students arrive in Santiago de Compostela. They make their way down narrow cobbled streets to the celebrated Obradoiro Square, where they are met with a cold, relentless wind and a cathedral almost hidden behind tall towers of scaffolding and plastic sheets. The nasal sound of a bagpiping busker cuts through the crowded square. The arrival is underwhelming, but as their eyes adjust, the undercurrents of emotion become visible: bikes clattering to the ground after weeks of grueling travel, fizzy champagne skyrocketing out of bottles, shouts of elation, tight hugs, arms straining to take selfies in front of the towering church. The students gaze out at this crowd of celebratory travelers, and their imaginations run wild with this vicarious experience.

“I wanted to feel the same excitement and sense of completion that they had,” Tenley Getschman says. “Our journey had been much different from theirs.”

Jackson Williams has similar feelings upon arrival: “All around were pilgrims crying, shouting, jumping and laughing as they’d finally reached their destination. In our group, there was a cautious approach. We cheated the Camino, after all.”

But, he says, “even though we hadn’t walked the Camino, it still felt like a finish line.” And there is no denying the spiritual significance of the place, regardless of whether one arrived on foot, by bicycle, by bus or otherwise.

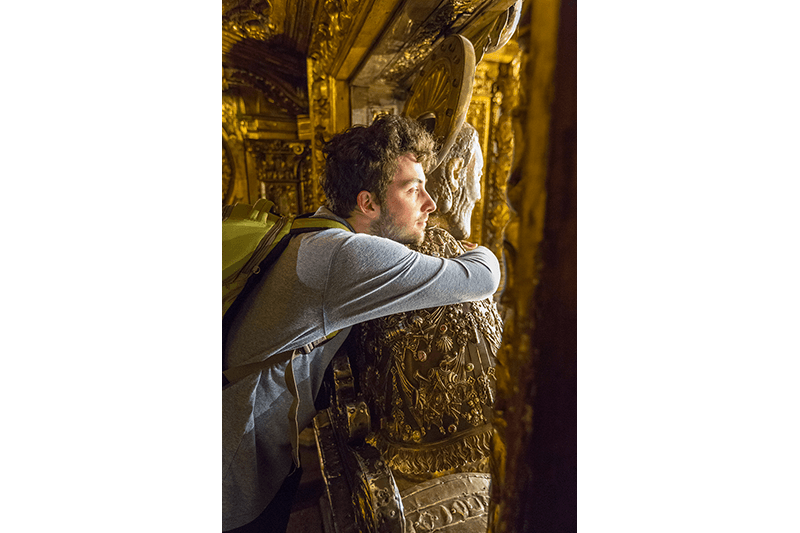

The students experience this spirituality first-hand inside the cathedral, where they join the queue to embrace a gilded statue of St. James on display in the apse. The gesture is a rite of passage for pilgrims completing their journey, and leaves some of the students in tears.

“I wrapped my arms around the statue and imagined the hundreds of thousands of pilgrims that had come before me, hugging this statue in this one-sided embrace,” recalls Williams. “It was an overwhelming moment. I felt a tightening in my chest that I still can’t quite explain, and I think I might have teared up.”

“It’s pretty amazing, don’t you think,” Dean Coon says in subdued tones beneath the giant hanging censor Botafumeiro, “that this place has the power to compel millions?”

Millions of pilgrims flock to Santiago, but many don’t stop there: the official end of the Camino is at Finisterre, on the western coast of Spain. This is where Jacob Huneycutt presents on that compulsive power that transcends time, pushing pilgrims to the End of the Earth. He stands before the calm, cobalt Atlantic, on a steep hill of rock and scrubby grasses. Beside him is a weather-beaten stone cross; a communications tower rises from the earth just a few feet away, underscoring his theme of pilgrimage past and present. Many aspects of pilgrimage have changed over the centuries, he says, but its meditative quality remains the same: “The act of walking turns the material into the immaterial. You feel that your body and life are the nexus between the heavens and earth, and also between the self and the environment, and that transcendent experience is very spiritual.”

In the small town of Najac, in France, Elizabeth Cooper and Tenley Getschman joked about the superficial changes that had overtaken them during the trip: “I bought my first V-neck! I can touch my toes now! I’m going to start wearing hats.” But as the trip progresses, the students become more serious about the small ways the Camino has challenged and surprised them.

“In Notre Dame, there was a small room off to the side. All they had was a very small statue of Mary,” reflects Curtis Worley, a freshman cultural anthropology major. “I’m not Catholic, not particularly religious, but I went in … and I just sat there. And for whatever reason, that was one of the most special moments. It was so surprising that something so small would mean so much.”

These small things add up until, even though the trip is over, many of the students aren’t ready to say goodbye to the Camino just yet. They may have developed an in-depth understanding of the highlights, but all this is just preparation for what is yet to come.

“My Honors Passport trip hadn’t concluded at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, it had started there. This was a revelation for me,” reflects Getschman in a blog post about the experience. “I will become a pilgrim later in my life. Using the far-reaching knowledge I have gained from my faculty and peers, I will one day traverse the Camino de Santiago in its entirety.”