By Kendall Curlee

Photos courtesy of Stephen Ironside and Quinn McHenry

The robots are here. New digital technologies drive innovation, Big Data is expanding the big picture, and the gig economy has kicked company loyalty to the far distant past. Thanks to COVID-19 lockdowns many of us are working remotely, scrambling to acquire new skills, or looking for new jobs. In their 2020 Future of Jobs Report the World Economic Forum noted that the pandemic-induced global recession has “created a highly uncertain outlook for the labour market and accelerated the arrival of the future of work.” All that uncertainty can produce nail-biting anxiety among ambitious honors scholars considering their options. But the current economy creates freedoms as well –– to do what you love to do, where you want to do it, on your own timetable. Here are three case studies of four University of Arkansas alumni who did just that, encountering a few twists and turns along the way.

Sweet Startups

“Do it! Go for it. Start small and iterate as many times as you need to.”

QUINN + AUSTIN SIMKINS: Natural Way Food Group

A cavernous, near-12,000-square-foot warehouse serves as headquarters for the Natural Way Food Group, and it’s mostly empty at the moment, except for some nut butter production machinery in one corner and a small office space near the front. But brothers Austin Simkins (B.S., agricultural business, ’14; M.B.A., supply chain management, ’17) and Quinn Simkins (B.S.B.A., accounting and finance, summa cum laude, ’18) have their eyes on the prize: The vision board in their office consists of one enormous photo of the peanut butter and jelly aisle at a local Walmart. This new warehouse is more than 10 times the size of their last space, made possible by the fact that they doubled sales of their nut butter line during the COVID-19 pandemic and brought on more than $1 million in investment funding this year. “Our goal now is, how quickly can we fill that place up?” Austin Simkins said.

Neither of the Simkins brothers planned a career in startups, but their business savvy emerged early on. They saved money from mowing lawns and doing other chores and deposited birthday checks in the bank. With help from their dad, they invested in stocks and made a tidy profit. Austin was the first to consider starting a business, inspired by a Walton College talk led by Startup Junkie’s Brett Amerine, who ended up becoming a friend, mentor and eventually, an investor. Simkins considered various business sectors and hit on food, because “everybody has to eat.” He recruited his brother and best friend Quinn, who’d gained some valuable experience as an intern at Tyson Foods. Discussions around the family dinner table led to their first product: the chocolate-covered peanut butter “poppers” that Austin and Quinn helped their grandmother make during the holidays. For startup funding, they turned to the more than $100,000 they’d saved and invested.

Simkins Brothers Sweets launched in 2017 and was a family enterprise from the get-go. “Grandma had an extra room in her house, and we created a makeshift kitchen,” Quinn Simkins recalled. “There was a stainless-steel table, a sink, and a chocolate machine that we bought for $5,000 — that was the most money I’d ever spent by far!” The brothers got a boost with two big wins in pitch competitions: They won $5,000 in the Collegiate National Ventures Competition and snagged first place and $10,000 in the IdeaFame contest with help from this pitch video. “That was a huge deal for us; any funding we could get helped, and it brought awareness,” Quinn said. That recognition, and a good product, helped them place their line in grocery stores throughout the region, including 250 Walmart stores.

Quinn’s honors thesis focused on the fledgling business and explored some new ideas: producing their own peanut butter to cut costs and creating a new product to differentiate them in the confectionary market. Enter Chirpies — chocolate-covered, gluten-free sweets made with cricket flour. “Cricket flour is an amazing alternative source of protein,” Quinn said. “I think 10 years from now it will be in lots of products.” But the crickets put off customers: “I guess we were a bit too early on that trend,” Austin said ruefully. Chocolate also proved to be a “finicky thing” to produce and ship, especially in Arkansas’ hot and humid summer months. In 2019, they dropped the Poppers and Chirpies to focus on their new “Natural Way” line of nut butters, made with olive oil rather than the palm oil found in many commercial peanut butters. “Olive oil is a healthier, more sustainable option than palm oil,” Quinn said. Austin added, “We like to be outside, be active, and we wanted to be in the natural food space — we can be more passionate about that.”

To date, they’ve expanded their line of nut butters to chain and independent grocery stores throughout the region, with accounts landed in California and the Pacific Northwest as well. They continue to tinker with new products, new packaging and — possibly — selling and starting a new company, but one thing is for sure: The Simkins brothers will stick with startups for the foreseeable future, and they think you should give it a go as well. “Do it! Go for it. Start small and iterate as many times as you need to,” Austin Simkins said. “The entrepreneur community is amazing here, full of people who want to see others win.”

From Designing Structures to Documenting Injustice

“…while thinking about design solutions, bigger questions about the politics of space emerged.”

LENIQUECA WELOME, Trinity College Anthropology Department

Leniqueca Welcome came to Arkansas to study architecture because she loved buildings and spaces. By the time she graduated in 2013, she was more drawn to the stories buildings tell than the structures themselves. For her honors thesis she looked home to Trinidad and Tobago to document the ways Trinidadians expressed their identity and their aspirations in their homes — a complicated business in a country with a complex composition of people due to the history of European colonization, chattel slavery and indentureship on the island.

“I came into architecture interested in finding simple ways to solve social problems through design. However, during the program, while thinking about design solutions, bigger questions about the politics of space emerged. My thesis was the start of my exploration of the relationship between power and space,” Welcome said. For example, she’d always been interested in low-income housing, how to build it better and at less cost. “I began to think through the bigger questions, like: ‘Why do we need these houses, why are people pushed to the margins, and why are the people requiring social housing predominantly Black and brown people?’”

Upon graduation, Welcome returned home to practice architecture and began to explore graduate programs in anthropology, a field first suggested to her by her honors thesis mentor, architecture professor Ethel Goodstein-Murphree. She connected with anthropologists at the University of West Indies, Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania and dove into a heavy reading list. Over time she realized, “This really seems like a space where I can ask the questions that I want to ask and have the freedom to do the kind of research that I might want to do.”

Welcome found her niche at the University of Pennsylvania, where she recently completed her Ph.D. with a dissertation titled “Where Life is Precious: The Terrains of Criminalization, Violence, and Freedom in Trinidad.” In preparation she conducted 18 months of field work to better understand how the state, the media and civil society in Trinidad dehumanize people living in certain areas of the capital city, Port of Spain. “So, whether you’ve been proven to commit a crime or not, because you come from particular geographies, because you look a certain way, other citizens watch you in a particular way that exposes you to more interactions with the police and possibly, these interactions ending fatally.”

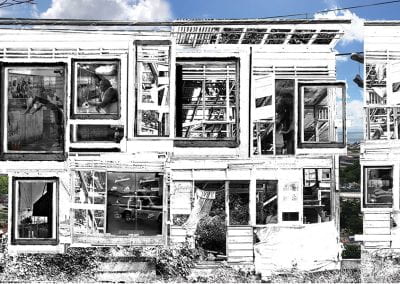

During those 18 months Welcome followed community police, worked with residents in communities labeled as hot spots, interviewed crime reporters and partnered with state agencies. She also photographed community members and created collages that explore issues of race, class, power and freedom. The collage below, for example, documents the site where a young man suspected of criminal activity was slain by a special branch of the police who had been surveilling him. “I ran into the relatives of the man killed by police, and they took me to the site,” Welcome recalled. Her collage commemorates the murder but makes a key change: “Instead of opening to the fishermen’s locker where he was killed, now it opens into water, which speaks to some form of repair or healing from that really tragic event.”

Given the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd, Welcome’s research speaks to our time. “There’s not really an escape into work for me, but that’s also the rewarding part,” she said. “I hope that the work I do can contribute to other work, in the academy and by activists, to dismantle systems of oppression and make transformation possible.” Welcome plans to continue her research and mentor the next generation of scholars and activists in her tenure-track position in the anthropology department at Trinity College in Connecticut. And it turns out, Welcome’s early training at the University of Arkansas has equipped her well for this effort: “Architecture really taught me to imagine something that doesn’t exist, to try to make it real.”

Images, clockwise from left: Over-exposed, photographic collage, 2020 / Roadblock, photographic collage, 2020 / Graphic design work.

Setting the Stage at the New York Times

“Diving deep into arts and science, and being okay with a little ambiguity and uncertainty, can pay off in a way that you won’t be able to predict.”

DREW COGBILL, The New York Times

As technical product director at the New York Times, Drew Cogbill is shaping our online experience of news, games and food at a company that leads in digital content creation. His team’s work may lack the flash and glamor of writing groundbreaking articles and taking change-the-world photos, but the software developed by his team anchors how the Times tells its stories and how we consume them. “My team is building the stage, and other teams perform on the stage,” Cogbill said. “The newsroom — they play the instruments.”

His trailblazing work in online applications veered from a more conventional path. Cogbill came to the U of A set on becoming a doctor and successfully completed an honors thesis in chemistry, “Synthesis of Hollow, Porous Titanium Dioxide Microspheres.” Although he enjoyed learning what scientific research looked like and working with lab members from around the world, it “didn’t totally land for me.” Cogbill was among the first group of Honors College Fellows, which supported wide-ranging exploration of many interests, including singing and musical theater. Gifted with a fine baritone voice, he sang in the chorus of Sweeney Todd, acted in Big Love and assisted theater professor Amy Hertzberg in directing productions of Into the Woods and I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change. This theatrical experience “really influenced the way that I lead teams,” Cogbill said, as did his vocal studies with professor emerita Janice Yoes. “I spent many hours honing my craft with her, and I think that influenced how I communicate, and also how I mentor and work with people.”

Upon completing degrees in chemistry and music, summa cum laude, in 2006, Cogbill had amassed plenty of experience in research and leadership but still wasn’t sure about a career in medicine. Together with his girlfriend, now wife, Danis Copenhaver (B.S., biochemistry, summa cum laude, ’06), he embarked on a gap year in Dangriga, Belize, where the couple was instrumental in laying the foundation for the U of A’s first and longest-running service-learning program. Belize also set Cogbill on his current path: “I was working in the mayor’s office, and they wanted a new website to promote tourism, and I thought, ‘Well yes, I can do that.’” Cogbill had taught himself how to code as a Boy Scout in junior high, and he managed to build a functional site using Dreamweaver and some additional coding to get the job done.

Buoyed by that experience, Cogbill applied to Parsons and started there right after Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, which in turn birthed a new industry of mobile applications. He dove deep into mastering user experience and developed puzzle games for Nokia and iPhones. “I knew I wanted to stick with things mobile but didn’t know how to build a career out of that,” he recalled. Quite by chance, a friend tipped him off to a new mobile company that was hiring. Cogbill applied and landed a job at Small Planet, where he experienced an auspicious start: On his first day, Disney hired them to build a storybook experience about Toy Story on a new platform that had just come out, the iPad. Cogbill’s work at Small Planet eventually grew to higher impact work for healthcare and e-commerce firms and propelled him to his current gig at the New York Times.

Buoyed by that experience, Cogbill applied to Parsons and started there right after Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, which in turn birthed a new industry of mobile applications. He dove deep into mastering user experience and developed puzzle games for Nokia and iPhones. “I knew I wanted to stick with things mobile but didn’t know how to build a career out of that,” he recalled. Quite by chance, a friend tipped him off to a new mobile company that was hiring. Cogbill applied and landed a job at Small Planet, where he experienced an auspicious start: On his first day, Disney hired them to build a storybook experience about Toy Story on a new platform that had just come out, the iPad. Cogbill’s work at Small Planet eventually grew to higher impact work for healthcare and e-commerce firms and propelled him to his current gig at the New York Times.

Luck? Sure. Good timing? Absolutely. But Cogbill is quick to credit his wide-ranging exploration here at the U of A for helping him find his way to a brand-new industry. “Diving deep into arts and science, and being okay with a little ambiguity and uncertainty, can pay off in a way that you won’t be able to predict.”